The text discusses the need for a reevaluation of the education system in light of technological advancements and changing societal norms. It highlights the limitations of a standardised approach to delivering knowledge and the unfairness it can create. The text also emphasises the importance of education in addressing global challenges. It calls for a more adaptive and technology-driven educational system that provides individualised learning experiences and prepares students for the rapidly evolving world. Additionally, it suggests that education needs to be funded adequately, redefined, and cooperatively integrated with other institutions to remain relevant and effective in shaping future generations in a human-focused world.

There is a standardised method of delivering knowledge across all educational establishments. No matter whether you attend private or public school in Britain or elsewhere in the world, we would all have learnt via textbooks, presentations, essays, books and tested our knowledge through some examination papers. It seems fair that all students should be delivered knowledge in an equal manner, and tested equally to measure who is more academically able in this or that subject compared to others.

There is a standardised stereotype that students do not like learning or attending school. Waking up for school at 8 am is perceived as a bore, and attending classes as a chore. Those who perform better academically pride themselves on their grades, and may find more motivation for attending and engaging in classes; those at the lower end of academic excellence are emotionally discouraged to engage with academia, either priding themselves on other abilities like sports, or disregarding school altogether. Interestingly, the teacher-parent discussions, the parent-child pressures, the ADHD pills or vocational schools never seem to be a resolution for dragging the lower performers in class up the grade ladder.

To me, these two aspects seem to be inherently intertwined. I disagree that a standardised method in delivery of knowledge and its assessment is fair, and I believe that students are not engaged with learning because they are not stimulated enough by their school. Stimulation does not come in the form of pretentious conversations like ‘people have different gifts,’ or of pressure to succeed, or of medication. Stimulation comes from inciting students to engage with the content, making it appealing for students to learn and making the school environment fun and individually adherent. Disabled students, for example those who are blind, are not given textbooks to read from, and those with paralysis are not encouraged to climb a flight of stairs to attend class; does that mean that education splits students only into those who are physically disabled and those that are not?

This stereotype comes from our evolutionary aspect, which we have used to separate people for the longer part of our history, which to me, falls in line with the other discriminatory views of our society such as racism and gender segregation. However, as the fields of psychology and neuroscience continue to develop, and we are getting further insights into the workings of our brains, the scientific community (at least) begins to realise that there is no standard to cognition. Whereas, in other forms of discrimination our society tries to improve, such as creating gender-neutral bathrooms, trying to close the gender-pay gap and punishing racist attitudes, the educational establishment is lacking behind. We are not standardised people, and we do not learn in standardised ways.

It is ironic that the educational establishment, where we develop from senseless children to active participants of society, is inherently flawed. After all, it is in school that we are socially orientated, learn that bullying is not acceptable, read about the latest developments of the world, and yet the schools themselves do not adapt any of these morals or practices. Schools have rankings of children who perform better than others academically (sometimes making them public) - not very pro-social; schools suggest that it is the students’ fault when they are not engaged in a class and consult parents on reprimanding them for their behaviour, or drugging them - seems like bullying to me; schools still use the same standardised method of teaching although technology has developed enough to provide alternative methods of teaching and latest scientific breakthroughs scream that the educational model is outdated.

On the counter-argument, of course, there are significant hurdles posed to education that prevent it from developing in this direction. Education is a significantly underfunded sector, with the share of expenditure from the national budget on education decreasing over the years in the UK (House of Commons, 2021); and private schools and universities actually being classed as charities as even the always-increasing tuition fees do not sustain them, and them having to live off donations of the alumni community. Do you know whose governments’ expenditures have been increasing over the years? China and India (Our World In Data, 2016). This is not a reprimanding article of the education system - this is a call to action to start re-designing the education system in the West, and to do so now!

So where should we start? How do we redefine learning and assessment? What is the new role of education in society? What will the future of education look like?

So where should we start? How do we redefine learning and assessment? What is the new role of education in society? What will the future of education look like?

Let’s start from the end

In order to understand what direction to take, we need to understand where we are going. What the future of education will look like depends on the work that will be required in the future.

The latest reports show that by the year 2027, the professions expected to experience the largest growth are AI and Machine Learning Specialists, Sustainability Specialists, Business Intelligence Analysts, and Information Security Analysts (World Economic Forum, 2023).

Why so? Well, with the rapid development of AI, robotics, automation and the internet, much of the current physical labour carried out by humans will be replaced by machines; same will go for the lower cognitively engaging tasks. Many fear that such development will create mass unemployment, but that is nonsense. Just like with the creation of the computer, these technologies will not only create new avenues of labour, they will actually revolutionise labour to be more human-orientated. For the first time in our history, humans will no longer be the producers, the deliverers, the executioners and the creators of the world; we will be just the creators and the dreamers. Isn’t that what we’ve always wanted: to be gods? Humans will finally be relieved of the manual aspects of the world and have the time to focus on what actually makes us human - our emotions, creativity and reason. What will gods need to learn then?

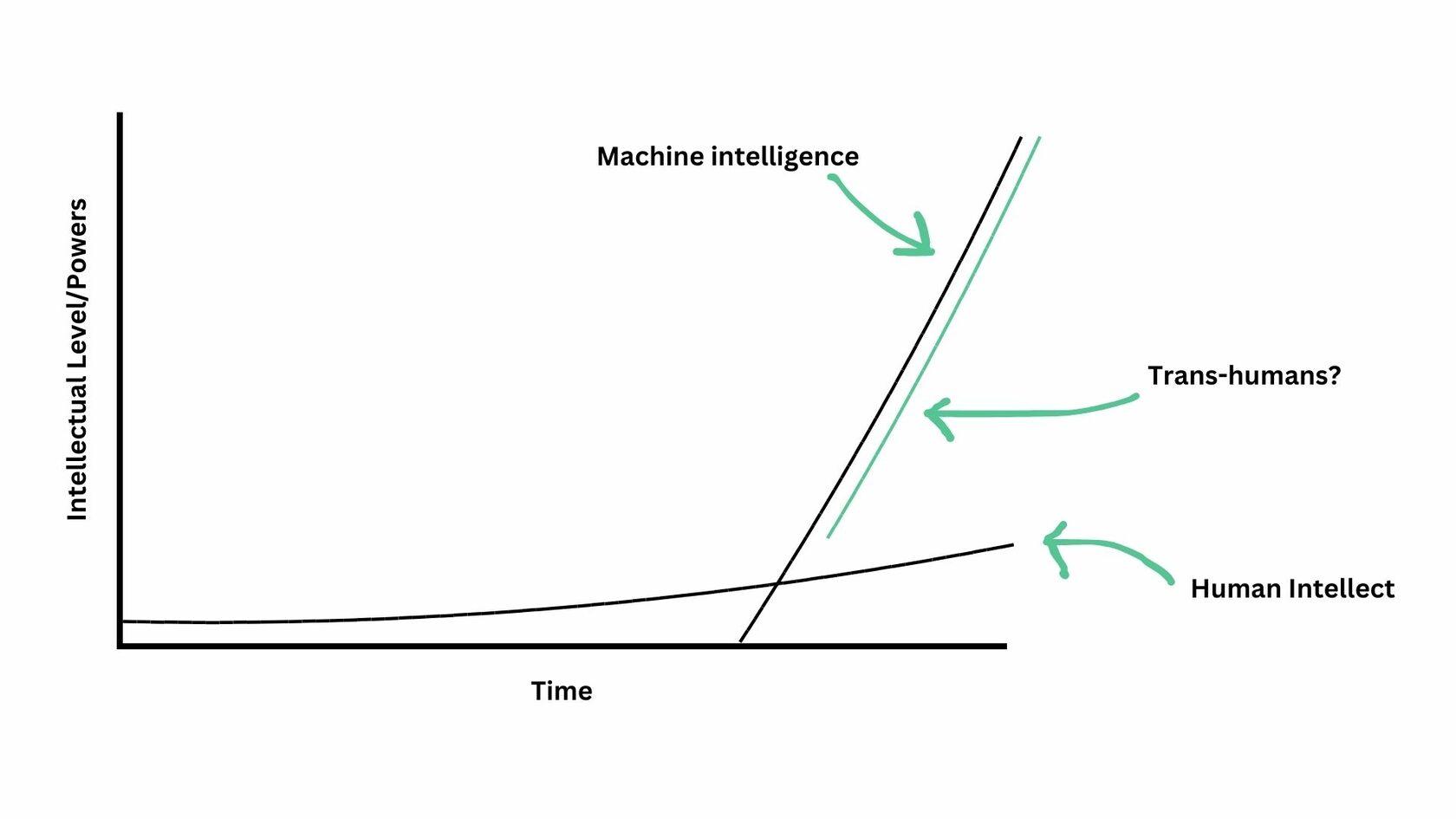

In a non-human-centric world, but in a human-focused world, technology will be developing faster than our biological minds (Singularity Point, Figure 1); therefore, it will be crucial that we keep up with the technological transformations of the world the best we can.

Education should no longer be a stage of upbringing in our lives that prepares us for the “outer world,” it should be an integral part of our society that stays with us throughout our lifespan.

Education should be an available resource as a basic human right (on TV channels at home, free university courses online, training and development sessions at work, etc.) As an example, this format would have ensured that your grandma today can navigate an iPhone with ease, understanding its functionality and need. In a human-focused world, where our persona and individuality are explored and valued more, education should inform humans on the pro-social behaviours and how participation and care of society ensures our sustainability, happiness and productivity. As an example, this format would have ensured that your racist grandpa today adopts the fact that it is no longer the 1950s and that the more acceptance there is in society, the better the productivity, the happiness and the progress of that society. Inevitably, technological advancements and the social structure are intertwined and as one develops, so does the other. For example, with development of understanding of the multiplicities of gender, gender confirmation surgeries have developed and been refined; contrastingly, with the development of the iPhone, cross-connectivity and long-distance human interactions have become a norm and have been refined.

It has been 77 years since the invention of the typewriter until humans have built the the first electronic general-purpose digital computer (ENIAC) in 1945; then it took just 39 years since to develop the first Mac, and since then it has taken 38 years for us to come to the invention of Artificial Intelligence today. In that time, we have gone from print media, to email, and now to giving machines their own autonomous intelligence (well, almost). Technological transformations have transformed society and vice versa, with exponential speed. In the future, such milestones will be accomplished in decades, then years and then maybe even days. Whereas the speed of technological advancements can be predicted by certain mechanical laws (such as Moore's law, for example), human biological advancement is very slow. Our only benefit is that our brains are malleable on a physical level, and are adaptive to make new neural networks, therefore forming new perspectives, ideas and thoughts. Education is the stimulating practice for this process and the faster we will have to adapt, the more of education we will need to have in our lives.

What new approaches will education take?

Just as technological advancements are being applied in the leading industries for them to thrive, so will the education sector need to make use of the latest tools to develop thriving minds. Many educational establishments are now actually going in the opposite direction, significantly slowing their chances of progress - you most certainly would have come across your school or university forbidding the use of AI. In the near future, AI will be everywhere, not only will it be used in literally every single aspect of our life, it will redefine the skills and knowledge that we will need to have as humans for success in our future employment. It is very clear, and ironically irrational, that this impasse stems from pure fear - the education system has been the same for many many years, as a reliable bridge standing there with the same road with the same function, to get you from point A (lack of knowledge) to point B (employment), and it has never failed, with only its potholes being fixed. Well, its first pillar has just collapsed.

It is simply out of the lack of understanding of how education may look that schools and universities are trembling in fear. The answer for them is the same as it is for every other aspect of our modern-day society: technology will solve everything. They just need to apply it.

Everything will have to be redesigned about what a school is, from its architectural structure, its physical to online format, to the roles of teachers and students in acquiring knowledge. It will be too long for me to share my perspectives on each of those, but let’s take a closer look at the individual approaches that education can take in delivering knowledge to students, which we talked about in the introduction.

In 1992, Neil D. Fleming and Colleen Mills published a research paper outlining the four modalities of learning: Visual, Aural, Read/Write, Kinaesthetic (Figure 2). The visual approach delivers information using maps, diagrams, charts, graphs, flow charts, and all the symbolic arrows, circles, hierarchies, and other devices that people use to represent what could have been presented in words. The aural approach refers to those who learn best from lectures, group discussions, radio, email, using mobile phones, speaking and talking things through. The Read/Write mode emphasises text-based input and output – reading and writing in all its forms but especially manuals, reports, essays, and assignments. The kinaesthetic form of learning includes demonstrations, simulations, and videos of “real” things, as well as case studies, practice, and applications.

The most applied learning method today is obviously Read/Write, and schools take little attention to those students who find other formats of learning better. And why should they? If you are not at one of the extreme ends of the autism spectrum and are not physically disabled, then you will anyways be assessed in Read/Write format. As discussed previously, this does not seem a fair approach. Students may be fascinated by biology, but 500 pages of black letters on white paper can quickly make them lose interest. Will watching footage of how DNA splits in real life or how neurons form connection incite them more? Will listening to a podcast that makes key information about the splitting of a cell rhyme before going to bed help students prepare better for their exam the next morning? You will probably say this is extreme, but this is something that is already being done, whether by AI or not. Netflix and Spotify have done more to revolutionise education in this sense than any school I know in the UK.

Imagine this. You attend a history lesson, where you have to learn 10 names of key figures at the Battle of the Waterloo. You have to also learn their birth years, the exact date of the battle, the battle strategies they used, who won and how. You can read scholarly articles on the topic, write all this information out, and repeat it endlessly until you can repeat it correctly without any longer understanding what you are really saying. Alternatively, you can put on Artificial Reality goggles (like the ones Apple recently released), you can ask AI to generate a film of the Battle of Waterloo, with you standing right in the middle of it, witnessing the battle first hand. Surely the latter approach will not only make the students learn better, but engage them more in the topic, incite an interest in the subject and actually make them eager to attend class?

You may think that this is all too advanced to think about now, but it is not. Today, David Attenborough and Neil deGrasse Tyson are doing shows on Netflix, I use AI to generate artificial videos, Apple and Meta are releasing artificial reality devices - all it takes is to combine this all. And what school, university or government are investing into these types of educational projects? China is, partly, but that is pretty much it.

You may think that this is all too advanced to think about now, but it is not. Today, David Attenborough and Neil deGrasse Tyson are doing shows on Netflix, I use AI to generate artificial videos, Apple and Meta are releasing artificial reality devices - all it takes is to combine this all. And what school, university or government are investing into these types of educational projects? China is, partly, but that is pretty much it.

So where and how do we start?

The education sector occupies a rather undefined niche in the collective conversation. Everyone understands that it is crucial, and almost all countries ensure that some level of it is compulsory.

However, as it has been working the same for so many years, nobody is talking about revolutionising it - very few people understand that the current education system will not be sustainable for our future societies (it barely is now), and if education fails, a lot of things will go wrong.

KhanAcademy, for example, is a beacon in this regard. Sal Khan’s TED talks are incredibly inspiring, and he is an activist for the right direction that education can take. Not only is he doing so much in revolutionising the field, simply by being an active voice for these changes, he is doing what Clevermagazine is set to do - revolutionise the discussion around education’s role in our society. The realisation of the problem, and speaking out about it is the first step on the route to transformation.

The education sector will need to become highly intertwined with other institutions. Like in the example of Netflix and Spotify, Apple and Meta, schools and universities will need to do more to invest in partnerships with these companies, creating opportunities for developers to direct their work at shaping young minds. The role of the teacher will need to become a highly valued position in society, a standard that has been forgotten over the years, kept only by a few Nordic communities today (interestingly their education structure is regarded as one of the best in the world). Moreover, the restructure of learning and assessment will be beneficial for future employers invested in or in partnership with that or the other school. Consider taking an interview for employment at Google, Starbucks and the University of Oxford. Google will be interested in your creative skills that you may have acquired from studying art, or from applying a multidisciplinary approach to tackle some problem; Starbucks will be interested in your communication skills, with the orientation toward working with clients; and the University of Oxford will test your knowledge and rigour that you have applied to your field of research. Besides their desired skills, all else that you have learnt at school will be of little interest to them. However, Google, Starbucks and the University of Oxford can design their own courses, practicals and assessments. They will shape young minds in the manner that is desirable to them as future employees, and they can trust the school to deliver on the other key aspects of shaping young minds (such as teaching them manners, pro-social behaviours, living in a community, etc). Furthermore, I am sure that a graduate course designed by Google will be attractive for other companies too, like Microsoft. Schools can pride themselves on the companies that sponsor courses at their establishments.

The education sector will need to become highly intertwined with other institutions. Like in the example of Netflix and Spotify, Apple and Meta, schools and universities will need to do more to invest in partnerships with these companies, creating opportunities for developers to direct their work at shaping young minds. The role of the teacher will need to become a highly valued position in society, a standard that has been forgotten over the years, kept only by a few Nordic communities today (interestingly their education structure is regarded as one of the best in the world). Moreover, the restructure of learning and assessment will be beneficial for future employers invested in or in partnership with that or the other school. Consider taking an interview for employment at Google, Starbucks and the University of Oxford. Google will be interested in your creative skills that you may have acquired from studying art, or from applying a multidisciplinary approach to tackle some problem; Starbucks will be interested in your communication skills, with the orientation toward working with clients; and the University of Oxford will test your knowledge and rigour that you have applied to your field of research. Besides their desired skills, all else that you have learnt at school will be of little interest to them. However, Google, Starbucks and the University of Oxford can design their own courses, practicals and assessments. They will shape young minds in the manner that is desirable to them as future employees, and they can trust the school to deliver on the other key aspects of shaping young minds (such as teaching them manners, pro-social behaviours, living in a community, etc). Furthermore, I am sure that a graduate course designed by Google will be attractive for other companies too, like Microsoft. Schools can pride themselves on the companies that sponsor courses at their establishments.

Conclusion

- Education is the number one driver of society: it is the place where children evolve into active participants of society.

- Our global society is currently experiencing a technological transformation.

- This transformation does not simply mean that one new technology will come into play and we will continue to live more or less the same for a long period of time until the next revolution comes along.

- This transformation will mean that more and more rapidly, the technology around us will evolve, creating new horizons, new problems and new ways of thinking.

- Technological advancements and societal norms have been intertwined throughout all of our history; as technology began advancing faster, so did our societal norms had to advance faster.

- The education system encompasses the progress that humans have made in acquiring knowledge in one or the other field, equipping us with the skills and latest knowledge to go into employment and discover new understanding in that or the other field.

- As technological advancements, and the intertwined societal adaptations, have been relatively slow, so did the education system remain almost unchanged, making reforms slowly.

- The technological revolution will exponentially accelerate these transformations meaning the education sector will not be able to keep up unless an adaptive education system is built.

- Signs of the education system failing are starting to show like the lack of individuality, the unfairness of standardisation, and the fear of adaptation to new technologies.

- The education sector is hindered in its reform due to lack of funding and public awareness/discourse regarding its role in society.

- The education sector needs to look to new avenues to find funding, and cooperate with other institutions to remain an integral cog in society, as well as redefine the niche it occupies in it.

There is this collective fear in the media right now about AI taking over the world. Although in my belief that is a hoax, the only resolve we hear is to pull the plug on its development. However, few realise that it is the development of education that will save us from falling victim to an AI takeover. At the time of social media, disinformation and AI development, we fear that the world’s development is out of our control. A few schools may host one lecture a year about online safety, how not to fall victim to propaganda or how to safely utilise AI, let alone a course on it. This shows already the extent to which this industry is falling behind. Many attribute potential global crises to physically evident things - viruses, asteroids, earthquakes, volcanoes, climate change, wars. In all of these fears, humans seem to miss out on the underlying factor that is the root of all these problems: human stupidity. And this problem will become evident to us only when it is too late as we will always blame everything but ourselves. In order to avoid falling into this trap, education needs to be taken care of. Have you ever heard the phrase ‘the pack is only as fast as its slowest man’?

References:

World Economic Forum (2023) - “Future of jobs report 2023.” Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf

Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2016) - "Education Spending". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/financing-education

Fleming, N. D., & Mills, C. (1992). Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflection. To improve the academy, 11(1), 137-155.

VARK (2023) - “The vark modalities: Visual, aural, read/write & kinesthetic.”. Available at: https://vark-learn.com/introduction-to-vark/the-vark-modalities/

House of Commons Library (2021) - “Education spending in the UK.” Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01078/

Singularity Leadership Development & Innovation Programs | Singularity. Available at: https://www.su.org/?_gl=1%2Aaucypw%2A_up%2AMQ..&gclid=CjwKCAjw15eqBhBZEiwAbDomEnB7tCk9EQgDak91zxg40GsZShXaBVTTrbFeLG961nJD8mc_s1gOvxoCRbUQAvD_BwE

World Economic Forum (2023) - “Future of jobs report 2023.” Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf

Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2016) - "Education Spending". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/financing-education

Fleming, N. D., & Mills, C. (1992). Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflection. To improve the academy, 11(1), 137-155.

VARK (2023) - “The vark modalities: Visual, aural, read/write & kinesthetic.”. Available at: https://vark-learn.com/introduction-to-vark/the-vark-modalities/

House of Commons Library (2021) - “Education spending in the UK.” Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01078/

Singularity Leadership Development & Innovation Programs | Singularity. Available at: https://www.su.org/?_gl=1%2Aaucypw%2A_up%2AMQ..&gclid=CjwKCAjw15eqBhBZEiwAbDomEnB7tCk9EQgDak91zxg40GsZShXaBVTTrbFeLG961nJD8mc_s1gOvxoCRbUQAvD_BwE